COVID-19 Pneumonia Associated With Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum and Pneumopericardium [1]

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which originated in Wuhan, China, is spreading around the world, and the outbreak continues to escalate. Clinical features of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) usually include dry cough, fever, diarrhea, vomiting, and myalgia (1-2). However, atypical presentation and complications are described (3, 4). The authors report a case of pneumopericardium, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous emphysema associated with COVID-19.

A 58-year-old nonsmoking man was admitted to IFEMA COVID-19 field hospital with seven days of fever, occasional cough, and anosmia. Initial physical examination only showed bibasilar crackles. Chest X-ray showed bibasilar pneumonia. Analysis revealed mild lymphopenia, and moderate D-Dimer, PCR, and LDH elevation. The rRT-PCR test was positive for 2019-nCoV. He started treatment with hydroxychloroquine-ceftriaxone.

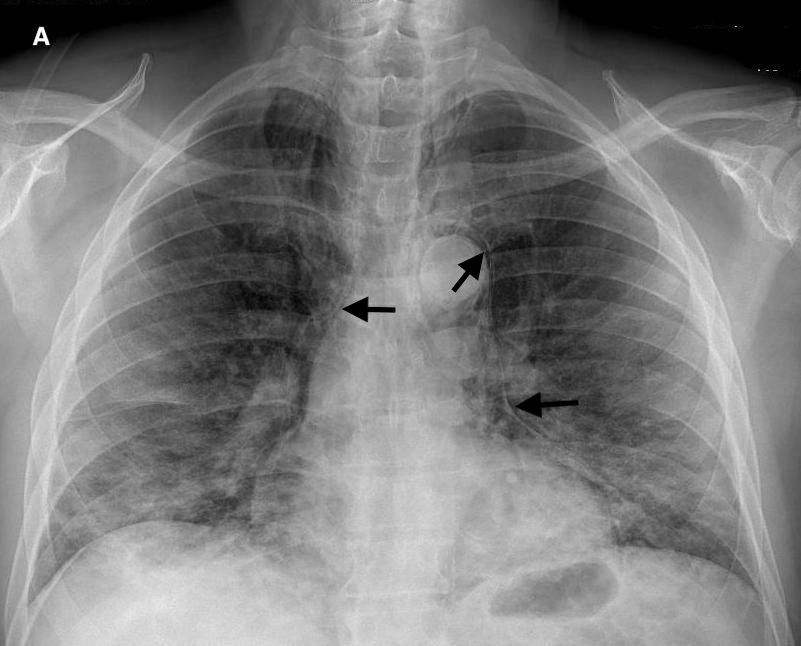

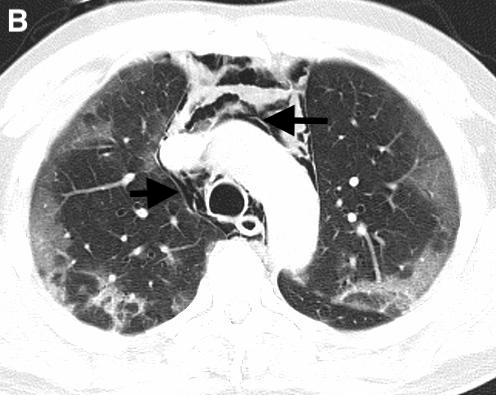

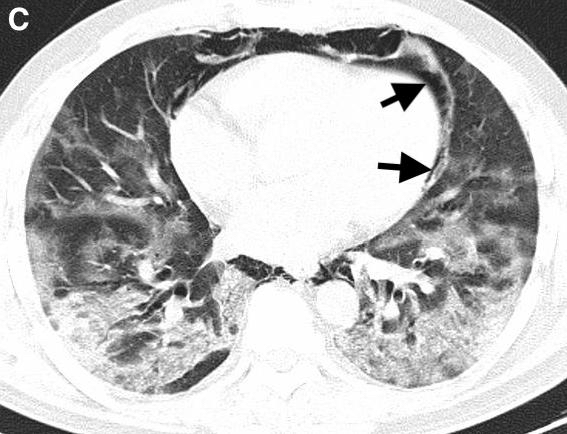

On hospital day five, the patient developed dysphonia, dysphagia, pleuritic pain, and subcutaneous emphysema in the supraclavicular region. His oxygen saturation was maintained at 97% with O2 at 3L / min through nasal cannula. A chest X-ray (Figure 1) and CT scan showed cervico-mediastinal emphysema (Figure 2) with pneumopericardium (Figure 3) and worsening lung infiltrates without pneumothorax.

The authors continued the same treatment and clinical-radiological follow-up. The patient maintained respiratory stability without increased oxygen requirements.Pneumopericardium is a rare condition, occasionally accompanied by pneumomediastinum, and is usually associated with positive pressure ventilation, thoracic surgery/pericardial fluid drainage, penetrating trauma, blunt trauma, infectious pericarditis with gas-producing organisms, and fistula between the pericardium and an adjacent air-containing organ (5).

Figure 3. [5]

Figure 3. [5]References

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. [6]

- Elsevier . 2020. Novel Coronavirus Information Center. [internet] Acceded 20th April 2020:

https://www.elsevier.com/connect/coronavirus-information-center [7] - G Toscano, F Palmerini, S Ravaglia, L Ruiz, P Invernizzi, M G Cuzzoni, et al. Guillain-Barré

syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 17. c2009191. [8] - Changyu Zhou, Chen Gao, Yuanliang Xie, Maosheng Xu. COVID-19 with spontaneous

pneumomediastinum. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Apr;20(4):510. [9] - Muñoz Avila JA, Jiménez Murillo LM, Montero Pérez FJ, Calderón de la Barca

Gázquez JM, Berlango Jiménez A, Durán Serantes M, et al. Pneumopericardium:

review of the literature. Rev Clin Esp. 1994 Oct;194(10):926-928. [10] - Cummings RG, Wesly RL, Adams DH, Lowe JE. Pneumopericardium resulting in cardiac

tamponade. Ann Thorac Surg. 1984 Jun;37(6):511-518. [11] - Giuliani S, Franklin A, Pierce J, HFord H, Grikscheit TC. Massive subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, and pneumopericardium in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2010 Mar;45(3):647-649. [12]

Disclaimer

The information and views presented on CTSNet.org represent the views of the authors and contributors of the material and not of CTSNet. Please review our full disclaimer page here [13].