ALERT!

This site is not optimized for Internet Explorer 8 (or older).

Please upgrade to a newer version of Internet Explorer or use an alternate browser such as Chrome or Firefox.

Facing the Challenges of Heart and Lung Harvesting and Procurement in Resource Limited Settings: Colombia

Vinck EE, Escobar JJ, Rendon JC. Facing the Challenges of Heart and Lung Harvesting and Procurement in Resource Limited Settings: Colombia. April 2024. doi:10.25373/ctsnet.25691376

Background

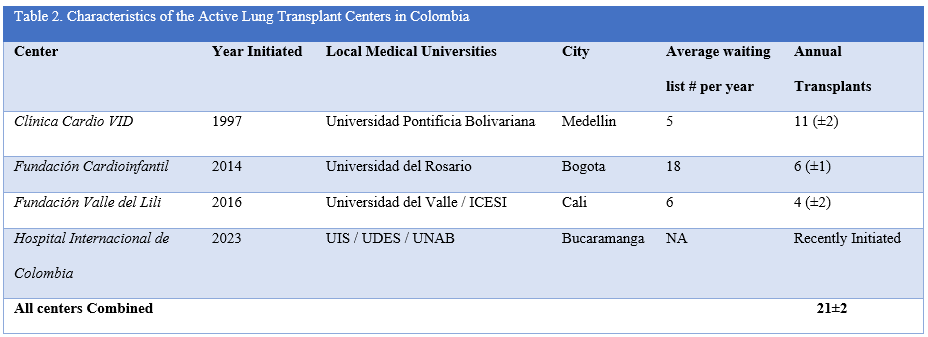

The first heart transplant in Colombia was performed in Medellín on December 1, 1985 and the first successful lung transplant in Colombia was performed on October 28, 1997 at the same center. The principal surgeon of these two milestones was Alberto Villegas Hernández (1, 2). Today, the Cardio VID Clinic at Pontifical Bolivarian University in Medellín, Colombia is still both the lung and heart transplant epicenter of Colombia. Currently, ten centers perform heart transplants in different cities in Colombia. Four of these centers have achieved sustainable lung transplant programs in association with their heart transplant divisions (Table 1–2). In Colombia, cardiac and thoracic surgery are different subspecialties, so heart transplants are performed by cardiac surgeons and lung transplants are performed by general thoracic surgeons. In Medellín, both cardiac and thoracic surgeons perform lung transplants (3–6).

Table 1

Table 2

General Cardiopulmonary Transplant Characteristics

The mean annual number of heart transplants in Colombia is 55±5 and 21±2 for lung transplants (3–6). The average number of patients on the national Colombian transplant waiting list is 21±2 for hearts and 32±2 for lungs, and waiting time is between 1–5 months—1.5 month at the authors’ clinic (3–6). Donor to recipient matching is arranged through a national network database and a multi-institution transport model. Once a heart and/or lung becomes available, a tissue match is determined by the transplant network protocol, including anatomy and HLA type matching. If emergency transplant criteria (INTERMACS II) are met in any city, the heart is procured and air bridged to the recipient’s city and center. If no national emergency transplant criteria are met, the heart or lung stays in the city where it has been harvested and is ground transported to the nearest transplant center (Figure 1). Procured lungs are kept within the same city limits for transplantation, as there is still no intercity lung bridging in Colombia (3–6).

Transplant center location influences outcomes. The four heart transplant centers located in Bogota are the only ones in the world based at 8,660 ft above sea level, with no apparent effect on survival (3). Air transport of the donor hearts to Medellín, Colombia, according to city of origin is as follows: from Bogota (415 kilometers), from Cali (417 kilometers) and from Bucaramanga (387 kilometers), all of which average 50 minutes air bridging time. Other nearby locations have transfers conducted through ground transport. The emerging nature of Colombia has led to many obstacles regarding survival. Suboptimal care of potential recipients, poor adherence to therapy, socioeconomic difficulties during post-transplant care and high numbers of traumatic donor deaths have all been significant factors influencing survival in Colombia (3–6). Many organ recipients also live in rural locations, impeding appropriate postoperative follow up with delayed identification of complications. This challenges prompt intervention. In addition, some health insurance companies have been inefficient in covering and providing immunosuppressive drugs.

Figure 1. Harvest Transplant Team transport van in Medellín, Colombia.

Healthcare Politics in Organ Harvesting and Transplant

Until recently, harvested organs in Colombia were transported in the harvesting surgeons’ cars. Of course, as safety protocols were increasingly emphasized and strictly implemented, more sophisticated transportation strategies and protocols were established. Because every minute counts when it comes to the time between harvesting and transplant, success rates depend on a national coordinated system rather than individual institutional strategies, economic characteristics, and approaches. Although the Colombian National Health Institute (INS) overseas organ designations and transplant processes, it does not directly impact transfer strategies. Many organs are transported either on ambulance ground transport, commercial airline flights, or emergency charter flights. Because of the many mountain ranges in Colombia, intercity ground transport is impossible. Heavy traffic can also make inter-center transfers difficult within the same city limits. Therefore, rapid air transport is critical in Colombia for harvesting-to-transplant success.

In Colombia, care disparities in health coverage do exist. The salaried population (contributive healthcare) receives 71–81 percent of heart and lung transplants, while the subsidized population (non-salaried and government funded) account for the remaining 18–22 percent of cardiopulmonary recipients. 82.4 percent of lung transplant recipients fall under the contributory branch of healthcare and 17.6 percent fall under the subsidized branch (3–6).

Despite immense efforts by the INS, cardiac transplant network, and centers, an average of four to five patients die annually on the national waiting list for a heart transplant in Colombia and seven on the lung transplant list (3–6). The high number of donor deaths caused by gunshot wounds (GSW) and head trauma reflects the grim public health and safety issues endemic to Colombia, also affecting graft quality and survival. An important achievement of the Colombian national transplant network is its minimal waiting times, resulting in swift donor-to-recipient matching and transplant. Also, these efforts and activities have resulted in an extremely low waiting list mortality. At the authors’ center in Medellín, patients rarely wait for more than one month for a transplant. The decreasing donor volume in Colombia is forcing a shift toward left ventricular assist devices (LVADs).

Harvesting Difficulties in Medellín, Colombia

Procuring heart and lungs in Medellín has its challenges. First, ground transport is quickly delayed due to traffic. Donor heart and lungs can become available from any number of hospitals within the Medellín county. Hearts procured from other cities must be brought to the medical center from the airport through an underground tunnel, which can easily be blocked. Because most lung transplant harvesting also includes cardiac extraction though the parallel heart transplant program, simultaneous cardiopulmonary harvesting is usually performed (3–6). Second, most procurement sites are under-funded public hospitals and other well established clinics, but without heart/lung transplant experience. As a result, these resource limited environments limit extraction support. Therefore, donors do not have preharvesting echocardiograms or bronchoscopies. Graft quality is, therefore, evaluated following sternotomy and visual inspection (3–6). Some hearts and lungs have been discarded after opening the donor chest, exhausting the transplant team and financially burdening the mobilized team.

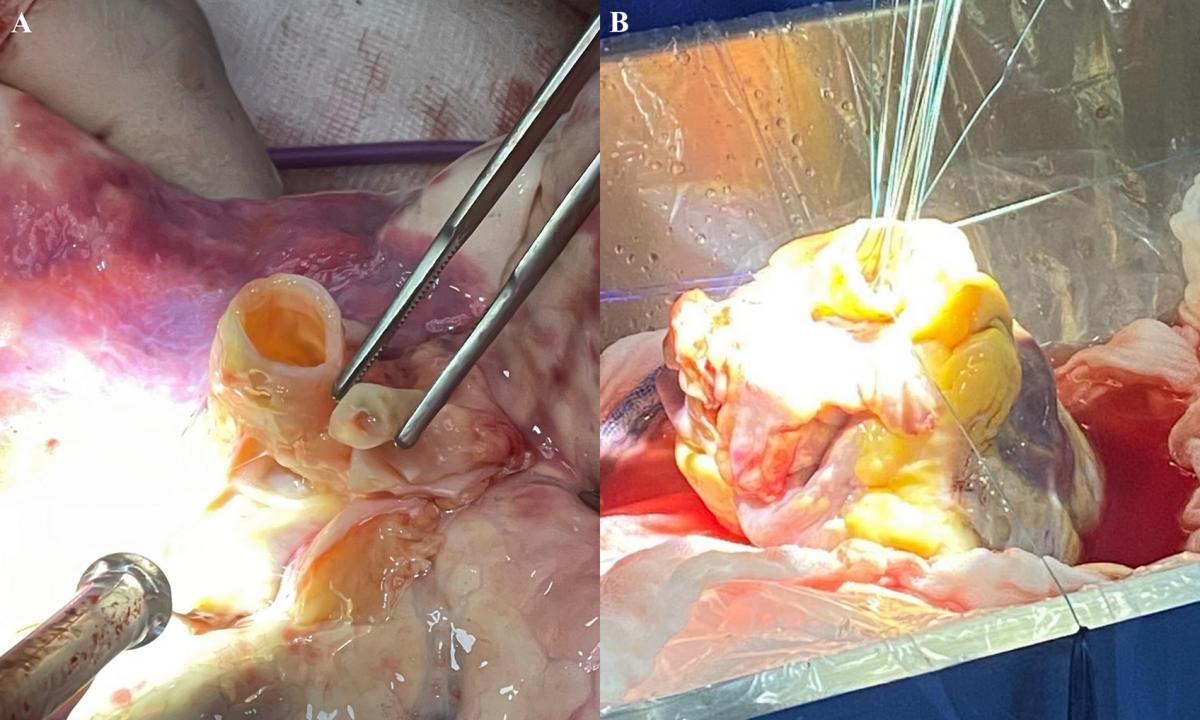

Figure 2A illustrates the case of a twenty-four-year-old male who suffered multiple gunshot wounds, including one to his head and one to his oral cavity. Upon being registered as a donor, the lung transplant protocol was activated, and the recipient was called to the authors’ clinic. During bench examination, surgeons found two teeth inside the left bronchus. The teeth were extracted, and the lung transplantation was performed without any complications. Figure 2B displays the case of a procured heart taken back to the authors’ transplant clinic. Upon bench examination, a severely stenotic and calcified aortic valve was found, requiring bench bio-prosthetic valve replacement prior to implantation (7). Once the extracting surgeons confirm the heart and lung grafts are adequate for transplantation, the transplant center is contacted, and the implanting surgeons begin recipient organ extraction. Ground transport from most harvesting sites to the authors’ transplant clinic usually takes 45–90 minutes (3–6).

Figure 2. A) Tooth retrieved from a Left bronchus during bench examination prior to Lung implantation. B) Bench aortic valve replacement due to severe valve stenosis and calcification found during bench examination.

Donor Characteristics

Median cardiac and pulmonary donor age in Medellín is 32.2 years. Donors are 33.9 percent female and 66.0 percent male. The principal donor causes of death are gunshot wound (26.1 percent), blunt head trauma (24.8 percent), motor vehicle accident (23.5 percent) and stroke (14.3 percent).

National healthcare coverage in Colombia reaches nearly 100 percent, allowing any person to be a transplant candidate (3–6). In Colombia, 100 percent of donated hearts and lungs remain in the country and are only transplanted to Colombians. Donor to recipient matching is made through each city and institution’s regional database and matching system (3–6). Upon donor identification and availability, matching is defined by international criteria and national transplant protocols, including HLA and anatomic characteristics. Because of progressive donor shortages both worldwide and in Colombia, marginal hearts and lungs may be used in select cases at the authors’ center (7). Advances and technologies such as ex-vivo to expand potential lungs still do not exist in the country.

Conclusion

Despite excellent transplantation healthcare coverage in Colombia, many factors specific to the harvesting and procurement process make the transplantation methods challenging. Socioeconomic hurdles such as under funding and lack of experience at harvesting sites along with technological shortages (echocardiograms and bronchoscopies) put donor heart and lung grafts at risk. The reliance on ground transport in all cities also makes ischemic time critical. In resource-limited settings, surgeons must emphasize impeccable bench examination to avoid implanting a diseased graft.

References

- Vinck EE. Cardiac surgery in Colombia: History, advances, and current perceptions of training. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;159(6):2347-2352.

- Vinck EE. General thoracic surgery as a subspecialty in Colombia. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2019 Jun;157(6):2542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.10.036

- Vinck EE, Rendón JC, Escobar JJ, Gómez AQ, Pérez LE, Cañas EM, Echeverri DA, Fernández RL, Quintero ÁM, Hernández AV. Thirty-five Years of Heart Transplantation in Medellín: Colombia's First Center for Cardiac Transplantation. Transplantation. 2022 Dec 1;106(12):2263-2266. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004159. Epub 2022 Nov 22.

- Vinck EE, Zapata RA, Rendón JC, Medina CM, Escobar JJ, Tobón MP, Colorado MF, Vargas AR, Uribe JD, Villegas AL. Twenty-five Years of Lung Transplantation in Medellín: Overcoming the Challenges of an Emerging Country. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023 Mar 13:S1043-0679(23)00037-0. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2023.03.001.

- Vinck E, Lind C, Lung Transplantation Challenges in Colombia: An Interview with Eric Vinck https://www.ctsnet.org/article/lung-transplantation-challenges-colombia-... July 25, 2023

- Vinck E, Mody G. Discussion to: Twenty-Five Years of Lung Transplantation in Medellín: Overcoming the Challenges of an Emerging Country. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023 Sep 18:S1043-0679(23)00097-7. doi:10.1053/j.semtcvs.2023.08.001.

- Rendón JC, Vinck EE, Quintero Gómez A, Escobar JJ, Suárez S, Echeverri DA. Bench bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement in a donor heart before transplantation. J Card Surg. 2022;1‐2. doi:10.1111/jocs.16519

Disclaimer

The information and views presented on CTSNet.org represent the views of the authors and contributors of the material and not of CTSNet. Please review our full disclaimer page here.