ALERT!

This site is not optimized for Internet Explorer 8 (or older).

Please upgrade to a newer version of Internet Explorer or use an alternate browser such as Chrome or Firefox.

Humanitarian Cardiac Surgery: A Trainee’s Perspective

Background

It is estimated that up to one in 100 children will be born with a congenital cardiac defect. This incidence may be even higher in developing nations where the capacity to care for the patients is low or completely absent [1]. In this regard, cardiothoracic surgeons have a long and storied history of humanitarian aid, and this is particularly true within the specialty of congenital heart surgery [2-7]. There are numerous reports within the literature that document the process, outcomes, and challenges of providing humanitarian surgical care to those who suffer from cardiac disease. However, there are no reports describing this process from the perspective of the trainee.

Planning Participation

Between the years of 2014 and 2015, I had the privilege of serving on two surgical missions. These missions were completed in Guayaquil, Ecuador, and Mirebalais, Haiti, during my general surgery residency. The process of obtaining this experience can be broadly divided into the following steps:

- Organization identification

- Institutional and American Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) approval

- Fundraising

While there are multiple organizations that provide humanitarian surgical care, there is little data available to the trainee with regard to which organizations support, or are willing to accept, residents on their missions. Therefore, I conducted a simple Internet search to find organizations that provide humanitarian cardiac surgical care. I then attempted to narrow this search to organizations that have a significant body of work and that conduct multiple missions per year, in order to increase the likelihood that I could take part in a mission at a time that would be acceptable for me to be away from my home institution.

Having completed my search, I then emailed and/or inquired online to each organization with a cover letter stating my interest and a copy of my CV. Responses were reviewed in terms of which organizations were willing to accept trainees and during which months missions were available. I ultimately joined The International Children’s Heart Foundation as a resident volunteer.

In order to secure time away from my training program, I was required to seek the permission of both my program director and the institution’s ACGME-designated institutional officer (DIO). Once this was secured, approval for the time away and the operative experience was obtained from ACGME.

At present, ACGME considers all international surgical rotations to be categorized as “elective” rotations, independent of whether the intent of the rotation is purely educational or humanitarian in nature. As such, approval for service on humanitarian missions must be completed through ACGME’s elective rotation approval process. This requires the completion of a paper-based application that covers over 20 individual points relating to the resident’s experience. I completed this application and mailed it to ACGME, as well as the American Board of Surgery (ABS). Decisions from these entities are received in approximately four to six weeks.

My application was ultimately denied, as ACGME noted that the supervising surgeon was not board certified within the United States. Therefore, the cases I was privileged to participate in could not be logged for training credit and the time spent away from my institution was ultimately charged as vacation.

There are significant costs related to providing humanitarian cardiac surgery. As it relates to individuals who volunteer, the primary costs associated with volunteering are: travel, lodging, board, and associated fees (passport, vaccinations, etc.). I secured funding for my trips through crowd sourced donations, my residency’s educational allowance, and grants provided directly by the sponsoring organization (ICHF).

The Clinical Experience

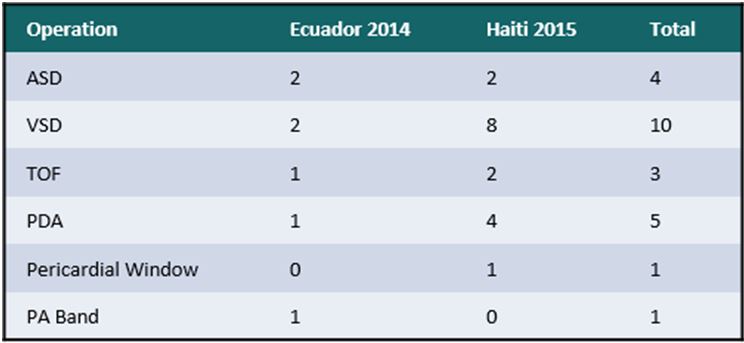

Ultimately, I served for one week in Guayaquil, Ecuador, in December of 2014, and for two weeks in Mirebalais, Haiti, in September of 2015. During the course of these trips I was able to participate in 24 congenital heart operations (Table 1).

The experience of serving on a cardiac surgery mission provided me with many unique opportunities. Arguably the greatest among these was early exposure to the specialty. Currently, ACGME and ABS require the general surgery resident to complete, at a minimum, 15 thoracic surgery cases in order to qualify for graduation and board certification. My home program, like many programs in the US, satisfies this requirement primarily through general thoracic surgery cases. Serving with ICHF gave me the chance to garner significant experience in the field of cardiac surgery. The number of cases I participated in was significantly more than the aforementioned ACGME/ABS requirements and is, in fact, greater than the 20 cases currently required by the American Board of Thoracic Surgery (ABTS) during the course of a cardiac surgery fellowship.

Impact

The impact of this experience on the general surgery resident cannot be overstated. Not only does it provide a solid foundation in the basics of open heart surgery, it also serves to increase the resident’s interest in the field and provides experiential motivation for the pursuit of a career in cardiac surgery.

There is, as well, a tremendous humanitarian impact to this experience. The burden of congenital cardiac disease in the developing world is an increasingly significant issue. For example, in Haiti there is no in-country congenital cardiac surgery program. The Haitian Cardiac Alliance estimates that there are approximately 1,500 children in the nation who suffer from congenital cardiac defects. For these patients, third party humanitarian aid is currently the only option for a surgical cure. Providing care to children with few other options showed me the potential impact of a career in cardiac surgery with dedicated humanitarian work.

Ongoing Challenges

Unfortunately, the process of participating in humanitarian surgical at the resident level is not without its challenges. The cost and the administrative components of the process remain prohibitive for many residents. The personal cost of a humanitarian mission can vary widely depending on location, and the price of travel, lodging, and meals. At a minimum, however, the volunteer can expect to need approximately $1,000 to offset the cost of his or her experience. I secured these funds through a combination of crowd-based fundraising and grants provided directly through ICHF, as noted earlier. The web-based product GoFundMe.com was utilized to raise funds, and awareness was generated through multiple social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, etc. I am fortunate enough to be surrounded by a supportive network of incredibly generous professionals. However, I am sure not all trainees are in such a fortunate position.

Administratively, in order for the experience to be deemed educational and the cases to count towards operative requirements, the trip must be processed through ACGME’s international elective application process. Presently, this application is processed on paper through the mail. ACGME also requires that the supervising surgical attending is board certified by the American Board of Surgery. This presents a challenge to residents seeking experience through humanitarian work. Surgical teams are often constructed of practitioners from across the globe and exposure to these different practice patterns is an exceptional educational opportunity for the trainee. In my case, the lead surgeon I worked with was of Chilean descent and trained in Chile, Australia, and France. This wide breadth of experience enabled him to provide a comprehensive education, but, ultimately, disqualified the experience from ACGME credit. As mentioned earlier, the time away from my home institution was charged as vacation.

These challenges are not without their solutions. The establishment of scholarships through various surgical societies could help to offset the cost to the resident and increase both awareness and interest in not only humanitarian cardiac surgery, but the cardiac surgery specialty as a whole. Also, ACGME’s process for approving these experiences could be made more efficient by moving towards a digital platform for submission and review. Further, ACGME could consider humanitarian rotations under separate criteria from international electives. For example, the review process could focus more intently on the organization with which the trainee travels rather than the organization or hospital where the group will work, and could include approval of rotations with international faculty, recognizing their contributions to the resident’s education. Ultimately, it will likely take the support of current practitioners to bring these changes to fruition. Again, surgical societies are in excellent position to provide guidance and aid.

Conclusion

Humanitarian work provides the surgical trainee with several unique opportunities. Among these are early and significant exposure to the practice of cardiac surgery and the chance to make a meaningful impact upon global health. Although the process of obtaining these experiences is challenging, it is well worth it.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Rodrigo Soto, Randa Blenden, and all the volunteers of ICHF for their time, assistance and education.

References

- Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(12):1890

- Nguyen N, Leon-Wyss J, et al. Paediatric cardiac surgery in low-income and middle-income countries: a continuing challenge. Arch Dis Child. 2015 Sep 10.

- Backer CL. Humanitarian congenital heart surgery: template for success. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014 Dec;148(6):2489-90

- Swain JD, Pugliese DN, et al. Partnership for sustainability in cardiac surgery to address critical rheumatic heart disease in sub-Saharan Africa: the experience from Rwanda. World J Surg. 2014;38(9):2205-11

- Thomson Mangnall L, Sibbritt D, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes after valve replacement surgery for rheumatic heart disease in the South Pacific, conducted by a fly-in/fly-out humanitarian surgical team: a 20-year retrospective study for the years 1991 to 2011. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148(5):1996-2003

- Maluf MA, Franzoni M, et al. The pediatric cardiac surgery as a philanthropic activity in the country and humanitarian mission abroad. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2009;24(3):VII-IX

- Kalangos A. "Hearts for all": a humanitarian association for the promotion of cardiology and cardiac surgery in developing countries. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(1):341-2.

Comments