ALERT!

This site is not optimized for Internet Explorer 8 (or older).

Please upgrade to a newer version of Internet Explorer or use an alternate browser such as Chrome or Firefox.

Laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication

Patient Selection

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders in the US today with a prevalence of 360/100,000 people. For the majority of patients this is a self limited condition that may be improved with changes in lifestyle or medical therapy. However, approximately 25% of patients with GERD will develop progressive disease that does not respond to simple therapy. Some of these patients may benefit from an antireflux procedure [1-4].

Some basic requirements for consideration for an antireflux procedure include complications of esophageal acid exposure such as stricture, Barrett's esophagus, and the presence of alkaline reflux. Other indications include persistent symptoms after 12 weeks of medical therapy and the inability to continue medical therapy [5,6].

We believe that all patients should have the following tests prior to surgery [2,4]:

- EGD with biopsies

- Esophageal manometry

- 24 hour pH study off acid medications (7 days off PPIs; 48 hrs off H2 receptor blockers). This is not required if the patient has a typical history of gastroesophageal reflux.

Some Patients may require:

- Barium esophagram

- Gastric emptying test

Operative Steps

|

| Figure 1: The operating surgeon stands between the patient's legs while the camera operator stands to the patient's right and the second assistant assumes a position on the patient's left. |

The patient is placed in a modified lithotomy position with the head of the table tilted up 25 degrees. The operating surgeon stands between the patient's legs while the camera operator stands to the patient's right and the second assistant assumes a position on the patient's left. Three 10-mm and two 5-mm trocars are placed as shown in Figure 1. The laparoscope is introduced through a port placed in the midline superior to the umbilicus. Placing the 5-mm trocars on either side of the midline allows for triangulation and avoids interference with the camera's line of vision.

The procedure begins with the exposure of the esophageal hiatus by the anterior retraction of the left lateral segment of the liver with a fan retractor. A Babcock clamp is placed on the esophageal fat pad and retracted toward the patient's feet. This exposes the gastrohepatic ligament and the phrenoesophageal membrane. A standard grasper and hook cautery are used to incise the gastrohepatic ligament and expose the right crus.

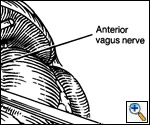

Care must be taken to identify and avoid damage to an aberrant left hepatic artery or to the nerve of Latarjet in the lesser omentum adjacent to the lesser curvature of the stomach. The dissection is then carried anteriorly until the left crus is identified.

The careful and complete dissection of the left crus and the angle of His are critical to developing the window posterior to the esophagus. The Babcock is repositioned to the 'shelf' of peritoneum which often attaches the fundus of the stomach to the diaphragm and left crus. Circumferential blunt dissection of the esophagus at the level of the hiatus will allow for the anterior retraction of the esophagus with the left hand dissector, allowing for further posterior dissection of the esophagus. The posterior 'window' is then identified with careful blunt dissection posterior to the esophagus just anterior and lateral to the left crus (Figure 2).

After the posterior 'window' is identified, a space just superior and medial to the free edge of the left crus is dissected free to allow for closure of the hiatus. This space is often referred to as the 'cave' (Figure 3). After the crura have been adequately identified and dissected free for a distance of 2 to 3 centimeters, the hiatus is closed using from 1 to 4 2-0 Prolene sutures (Figure 4). The esophagus is retracted anteriorly and to the left as the crura are approximated beginning at the level of the aortic decussation of the crura. Further bites are taken in an anterior direction until an adequate hiatal diameter is attained. This can be measured by placing a 56 Fr Maloney bougie in the esophagus or can be judged by experience. The sutures are tied extracorporeally using a standard knot pusher.

Attention is then turned to the short gastric vessels. A Harmonic scalpel is inserted into the right 5-mm port and a standard grasper is used to identify the gastrosplenic ligament. The Babcock is placed laterally to provide further exposure and retraction during short gastric ligation. The lesser sac is entered approximately one third of the way down the greater curvature of the stomach and the dissection is then carried out toward the splenic bed. Division of the short gastric vessels is assisted by further retraction of the stomach to the right and the gastric omentum to the left. With careful dissection, the fundus can be completely mobilized in most patients (Figure 5).

The Babcock clamp is then placed into the right most subcostal port and the clamp is passed into the posterior 'window' behind the esophagus. Graspers are then used to identify a point on the fundus approximately 15 cm distal to the Angle of His. This point is then placed into the open Babcock clamp and slowly pulled behind the esophagus through the 'window' (Figure 6). This portion should be released briefly once it is in position to ensure there is little tension. If it remains in position it has passed the 'drop test'.

Attention is then turned to the angle of His and the 'disappearing piece' of the fundus is identified going behind the esophagus. A clamp is used to grasp the appropriate portion of the fundus, close to the short gastric vessels, for the left side of the wrap. This anterior segment is approximated over the esophagus to the posterior fundus to ensure a snug wrap, which can be measured over a 56 Fr Maloney bougie or by experience. The 'shoe-shine' maneuver is used to ensure that the fundus slides freely posterior to the esophagus and is of appropriate length (Figure 7).

The wrap is then sutured into place using a single U-stitch of 2-0 Prolene buttressed with Teflon pledgets tied in an extracorporeal manner (Figure 8). The stitch incorporates the adjacent muscle layer of the esophagus. Care is taken not to place this stitch too deeply in the esophagus to avoid a full thickness injury to the esophagus should the patient retch after surgery. A 3-0 silk suture is used to further secure the wrap and is most easily tied intracorporeally (Figure 9). The suture line should lie to the right of the esophagus when finished. Finally, the abdomen is explored, hemostasis is assured, and the ports are removed under direct vision.

Postoperative Care

Patients are allowed to take liquids on recovery from anesthesia and are maintained on a diet of pureed foods for 1-2 weeks. Thereafter they can begin to take soft foods and go on to a normal diet after 4-6 weeks. Light activity is encouraged and heavy lifting is avoided for 4 weeks. Analgesia is given in liquid form for the first two weeks and all pills are crushed. Most patients are allowed to leave the hospital on the first postoperative day.

Preference Card

- Standard laparoscopy ports

- Standard 5-mm graspers

- 10-mm fan retractor

- 5-10-mm Babcock

- 5-mm harmonic scalpel

- suction irrigator

- free teflon pledget

- Sutures: 2-0 prolene

- 3-0 silk suture

Tips & Pitfalls

- While dividing the gastrohepatic ligament, look for an aberrant left hepatic artery.

- The fundus may lie just posterior to the left crus and can be perforated with blunt dissection of the posterior 'window'.

- Only dissect under clear vision. Always know what you are dividing or dissecting.

- Care must be taken while suturing the right crus to identify and avoid damage to the inferior vena cava.

- Caution should be used while suturing the crura and dissecting the hiatus as the aorta lies just inferiorly. There are reports of aortic injury.

- The spleen may easily be injured while passing the Babcock posterior to the esophagus and during aggressive short gastric division.

- While dividing the short gastric vessels, leave an adequate margin on the greater curvature to prevent injury to the stomach.

Results

Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is a well proven therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease, with over 90% of patients being highly satisfied on 8 to 10 year follow-up [7,8].

Complications include [9]:

| Wrap herniation | 1.3% |

| Pneumothorax | 1.0% |

| Perforation | 0.8% |

| Hemorrhage | 0.8% |

| Pneumonia | 0.6% |

| Abscess | 0.3% |

| Trochar site hernia | 0.2% |

| Pulmonary embolus | 0.2% |

| Splenectomy | 0.1% |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.1% |

Long-term side effect include dysphagia in 8%, abdominal bloating in about 10%, and new onset diarrhea in 14% of patients [8,10,11].

References

- Duranceau A, Jamieson GG. Hiatal Hernia and Gastroesophageal Reflux. In: Sabiston DC Jr, Lyerly HK, eds. Textbook of surgery: the biologic basis of modern surgical practice, 15th ed. Philadelphia. WB Saunders, 1997:767-783

- Hinder RA, Filipi CJ. Laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication. In: Cameron, JL ed. Current Surgical Therapy, 5th ed. St. Louis. Mosby, 1995:1063-1069

- Hinder RA, Filipi CJ, Wetscher G, et al. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is an effective treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg 1994;220:472-481

- Hinder RA, Libbey JS, Gorecki P, Bammer, T. Antireflux surgery - indications, preoperative evaluation, and outcome. Gastrointest Clin N Am 1999;28:987-1005

- Castell DO, Brunton SA, Earnest DL, Fogel R, Hinder RA, Liss D, Peters JH, Siegel MM. GERD: Management algorithms for the primary care physician and the specialist. Practical Gastroenterol 1998;4:18-46

- Glaser, K; Wetscher, GJ; Klingler, A; Klingler, PJ; Eltschka, B; Hollinsky, C; et al. Selection of patients for laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Dig Dis 2000;18:129-137

- Bammer T, Hinder RA, Klaus A, Klingler PJ. Five to eight year outcome of the first laparoscopic Nissen fundoplications. J Gastrointest Surg 2001;5:42-47

- Perdikis G, Hinder RA, Lund RJ, Raiser F, Katada N. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: where do we stand? Surg Lap Endosc 1997;7:17-21

- Carlson MA, Frantzides CT. Complications and results of primary minimally invasive antireflux procedures: a review of 10,735 reported cases. J Am Coll Surg 2001;193:428-39

- Malhi-Chowla N, Gorecki PJ, Bammer T, Achem SR, Hinder RA, DeVault KR. Dilation after fundoplication: timing, frequency, indications and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:219-23

- Klaus A, Hinder RA, DeVault KR, Achem SR. Bowel dysfunction after laparoscopic antireflux surgery: incidence, severity, and clinical course. Am J Med 2003;114:6-9