Introduction

Unilateral diaphragmatic agenesis is a rare diagnosis typically made early in infancy and generally associated with other genetic anomalies [1,2]. We present an unusual case of adult onset progressive shortness of breath and peripartum hepatic herniation into the chest, which on intraoperative exploration revealed diaphragmatic agenesis. We review the literature, propose preoperative imaging and describe an operative strategy.

|

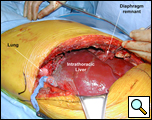

| Figure 1: Presentation chest x-ray revealing bilateral pleural effusions. |

Case Report

A 35-year old woman undergoing in vitro fertilization noted progressive shortness of breath, orthopnea, and moderate right lower chest discomfort worsening with deep inspiration. She subsequently presented to her gynecologist where ultrasound evaluation revealed ascites and bilateral pleural effusions (Figure 1). She was admitted for management of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. A contrast chest CT scan showed massive bilateral pleural effusions, loculated on the right with a small right pneumothorax. Bilateral thoracenteses were performed with drainage of 1300cc of serosanguinous fluid on the left and minimal fluid on the right.

Following clinical improvement she was discharged to home and a follow-up chest radiograph one month later revealed continued improvement in the left pleural effusion, but with persistence of a multiloculated hydropneumothorax on the right side. Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) demonstrated a restrictive defect with FVC of 2.1 (59% of predicted); and FEV1 of 1.61 (59% of predicted) and FEV1/FVC ratio of 0.77. Non-operative management was recommended and she continued to improve over the next few months. Patient successfully pursued pregnancy. At 20 weeks gestation (one year from her thoracentesis), she complained of shortness of breath with vigorous activity. She was found to have a resolved left pleural effusion and persistence of the right multiloculated hydropneumothorax on chest radiograph.

By 29 weeks of gestation, she was increasingly symptomatic with exertion and was found to have a slight reduction in her PFTs to an FVC of 2.07 (51% of predicted) and a FEV1 of 1.65 (49% of predicted). Non-operative management was again recommended and at 38 weeks gestation she delivered a healthy baby. However, her hospitalization was complicated by fever and elevated liver enzymes. An abdomino-pelvic CT revealed an enlarged and heterogeneous liver and loculated R hydropneumothorax. At 4 months follow-up, she was found to have persistently elevated liver function tests. A new CT scan revealed passive congestion in the right lobe and a three cm hypervascular lesion in the left lobe (Figure 2). Further evaluation with MRI revealed passive congestion of the right lobe of the liver with herniation into the thoracic cavity resulting in right hepatic vein compression at its junction with the inferior vena cava (Figure 3). Multiple additional lesions were felt to be consistent with fibronodular hyperplasia.

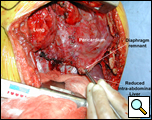

Consultation with general and thoracic surgery services agreed that operative correction was required due to progressive symptoms and partial hepatic vein obstruction. VATS revealed that the right lobe of the liver was entirely in the right chest, the margins of the diaphragmatic defect could not be seen, and there was no hernia sac (Figure 4). The right lung was trapped and there were multiple adhesions present.

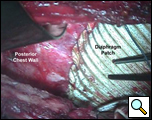

Through a 7th interspace right thoracoabdominal incision, the right lung was decorticated and pneumolysis performed (Figure 5). Once dissection was complete, the liver was found in the pleural space with only a small rim of diaphragm medially (Figure 6). The liver was completely mobilized and reduced into the abdomen, insuring that the right hepatic vein was not kinked. Multiple liver biopsies were obtained. The diaphragm was reconstructed using a 15x25cm 2mm thick polytetrafluoroethylene patch, anchoring it posteriorly near the 10-11th thoracic vertebral level to the posterior mediastinal fascia, laterally around the ribs, and anteriorly to the medial remnant of the diaphragm (Figure 7).

|

|

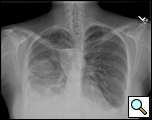

Figure 8: Postoperative chest CT scan reveals neo-diaphragm and reduction of the liver back into the abdomen. |

She made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on postoperative day seven. Pathologic examination of the liver revealed normal liver parenchyma with no diagnostic abnormality. The visceral and parietal pleural biopsies revealed chronic pleuritis. A postoperative CT scan revealed an intact diaphragmatic repair with the liver within the abdomen and the right lower lobe completely expanded (Figure 8). Patient has been seen in our clinic approximately 3 months following surgery with no recurrence of hepatic herniation, improved effort tolerance and no recurrence of her loculated effusion.

Discussion

Diaphragmatic agenesis is typically diagnosed very early in infancy and carries a significant mortality of up to 38 - 62% [1, 2]. Survival of these infants often depends on cardiopulmonary function and the constellation of other congenital anomalies that is often present. The development of the diaphragm occurs early in gestation via a fusion of the embryonic pleuroperitoneal membrane and the transverse septum. During the third week of gestation, the fusion of the transverse septum with the dorsal mesentery of the foregut creates two openings whereby the thoracic and abdominal contents meet. During the ninth week of gestation, these openings close. Thus any process inhibiting the closure of these channels may lead to defects in the diaphragm [1], including congenital diaphragmatic hernia, hernia of Morgagni, and diaphragmatic agenesis. Isolated diaphragm agenesis is rare. It does however, occur with familial heritance with often multifactorial genetic etiologies [3-5].

Five cases in the literature have documented diaphragmatic agenesis (Table 1). The first reported case of diaphragmatic agenesis was described in 1988 by Tzelepis et al. from the Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island with a patient that presented with a persistent left lower lobe infiltrate that was ultimately determined to be complete absence of the left hemidiaphragm [6]. While most symptomatic adult patients with left-sided diaphragmatic defects present with symptoms of visceral herniation [7, 8], it is believed that right-sided agenesis occurs with few symptoms due to the presence of the liver preventing other viscera from herniating through the diaphragmatic defect. It is likely that our patient had no symptoms prior to pregnancy as the liver remained within the abdominal cavity until displaced by the gravid uterus. Our case is the first report of liver enzyme abnormality and hepatic venous obstruction in a patient with right-sided diaphragmatic agenesis.

Table 1: Patient Clinical Presentation and Diagnostics

| Author | Presentation | Diagnostic Imaging Modality | Laterality | Visceral Herniation |

| Tzelepis [6] | Persistant left lower lobe infiltrate | Barium enema, Upper GI series, and CT scan | Left | Colon and small bowel |

| Singh [18] | Left sided chest pain Dyspnea Abdomial pain Vomiting Constipation |

Chest X-ray | Left | Stomach, spleen, small bowel, and colon |

| Singh[18] | Asymptomatic | Chest X-ray and Upper GI series | Left | Stomach |

| Travaline[1] | Asymptomatic | Chest X-ray, MRI | Right | Colon, small bowel, and right kidney |

| Wakai[17] | Dyspepsia, right upper quadrant Abdominal pain |

Chest X-ray, Abdominal ultrasound | Right | Elevated and rotated liver, colon, omentum |

| Komanapalli | Persistant right pleural effusions | MRI | Right | Liver |

Diagnostic imaging modalities to assess diaphragmatic agenesis range from routine chest radiographs to magnetic resonance imaging. Patients who are diagnosed with the defect on routine chest x-ray often present with obstructive symptoms and are found to have intrathoracic visceral herniation. Contrast radiography (upper GI series or enema studies) may be of assistance in determining the presence of intrathoracic bowel herniation. Solid organ herniation may be more difficult to diagnose and may require computed tomography. Further imaging is necessary when symptoms are more subtle or patients are asymptomatic. In these instances, thin slices and multiplanar images (3-D reconstructions) can assist in the making the diagnosis. It is unclear why the CT scan was non-diagnostic in our patient; however in studies of traumatic diaphragmatic tears CT has limited diagnostic utility [9-11]. In these studies, sagittal and/or coronal MR imaging or spiral CT scan with coronal and sagittal reformatting can be definitive [10, 12-15]. Ultrasound may be of complementary value by demonstrating the free edge of the diaphragm defect within pleural fluid or demonstrating liver herniation [16].

The management of right-sided diaphragm defects is controversial. In the trauma literature, patients who present with right-sided herniation can often be managed non-operatively because the liver prevents visceral herniation. However, patients with right-sided agenesis may require operative intervention to prevent liver herniation as well as other abdominal organ herniation [1, 17]. Patients who are symptomatic with dyspnea, recurrent pleural effusions, or organ herniation will require operative intervention to prevent organ damage or prevent worsening of pulmonary function [18]. A thoracotomy or thoracoabdominal approach provides good exposure and access to the abdomen if needed [6, 18]. Reports of reconstruction are varied in their use of material ranging from suture of the diaphragmatic margins to the lobe of the liver, free skin grafts, abdominal muscle flaps and prosthetic material [18-20]. Reconstruction can be performed with prolene mesh or a PTFE patch, anchoring the prosthesis to the chest wall using heavy 0 or #1 non-absorbable sutures in an interrupted or running fashion.

Conclusion

Diaphragm agenesis is an exceedingly rare diagnosis in the adult population. The definitive imaging diagnosis of diaphragmatic agenesis requires a high index of clinical suspicion in that routine studies may miss subtle evidence of diaphragmatic defects. Repair of right-sided defects is necessary in symptomatic patients to prevent decline in pulmonary function and or prevent visceral herniation. In women of child-bearing age, repair of diaphragm agenesis may be warranted even when asymptomatic to prevent visceral herniation during pregnancy.

References

- Travaline JM and Cordova F. Agenesis of the diaphragm. Am J Med. 1996;100:585.

- Valente A and Brereton RJ. Unilateral agenesis of the diaphragm. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:848-50.

- Gualandri V, Lalatta F, Orsini GB, Zorzoli A, Bertagnoli L, and Gallicchio R. Prenatal diagnosis of a case of familial recurrence of unilateral diaphragmatic agenesis. J Genet Hum. 1983;31:125-31.

- Sripathi V and Beasley SW. Familial occurrence of complete agenesis of the diaphragm. J Paediatr Child Health. 1992;28:190-1.

- Toriello HV, Landenburger G, Kapur SJ, and Higgins JV. Isolated diaphragmatic defect in three sibs. Am J Med Genet Suppl. 1986;2:177-81.

- Tzelepis GE, Ettensohn DB, Shapiro B, and McCool FD. Unilateral absence of the diaphragm in an asymptomatic adult. Chest. 1988;94:1301-3.

- Ghanem AN, Chankun TS, and Brooks PL. Total gastric gangrene complicating adult Bochdalek hernia. Br J Surg. 1987;74:779.

- Sugg WL, Roper CL, and Carlsson E. Incarcerated Bochdalek hernias in the adult. Ann Surg. 1964;160:847-51.

- Chen JC and Wilson SE. Diaphragmatic injuries: recognition and management in sixty-two patients. Am Surg. 1991;57:810-5.

- Gelman R, Mirvis SE, and Gens D. Diaphragmatic rupture due to blunt trauma: sensitivity of plain chest radiographs. Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:51-7.

- Voeller GR, Reisser JR, Fabian TC, Kudsk K, and Mangiante EC. Blunt diaphragm injuries. A five-year experience. Am Surg. 1990;56:28-31.

- Carter EA, Cleverley JR, Delany DJ, and Lea RE. Cine MRI in the diagnosis of a ruptured right hemidiaphragm. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:137-40.

- Dosios T, Papachristos IC, and Chrysicopoulos H. Magnetic resonance imaging of blunt traumatic rupture of the right hemidiaphragm. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1993;7:553-4.

- Mirvis SE, Keramati B, Buckman R, and Rodriguez A. MR imaging of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1988;12:147-9.

- Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, White CS, and Pomerantz SM. MR imaging evaluation of hemidiaphragms in acute blunt trauma: experience with 16 patients. Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:397-402.

- Gierada DS, Slone RM, and Fleishman MJ. Imaging evaluation of the diaphragm. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1998;8:237-80.

- Wakai A, Winter DC, and O'Sullivan GC. Unilateral diaphragmatic agenesis precluding laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Jsls. 2000;4:259-61.

- Singh G and Bose SM. Agenesis of hemidiaphragm in adults. Aust N Z J Surg. 1993;63(4):327-8.

- Scaife ER, Johnson DG, Meyers RL, Johnson SM, and Matlak ME. The split abdominal wall muscle flap--a simple, mesh-free approach to repair large diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1748-51.

- Shaffer JO. Prosthesis for agenesis of the diaphragm. JAMA. 1964;188:1000-2.