ALERT!

This site is not optimized for Internet Explorer 8 (or older).

Please upgrade to a newer version of Internet Explorer or use an alternate browser such as Chrome or Firefox.

Thoracotomy for Exposure of the Spine

Patient Selection

The initial selection is performed by the spine surgeon for typical indications of spine stabilization, resection of tumor, drainage of an abscess, and re-operation for complications of previous spine surgery [1-3]. The transthoracic approach (thoracotomy) affords the spine surgeon excellent visualization and access to the anterior thoracic spine, the vertebral bodies, intervertebral disks, spinal canal, and nerve roots. Only the contralateral pedicle and posterior elements are inaccessible through this approach.

The approach is currently used in the surgical treatment of thoracic disk disease, vertebral osteomyelitis or discitis, fractures of the spinal column, and tumors of the vertebral bodies, allowing for proper decompression of neural elements and spine stabilization.

The first reported series of thoracotomies for transthoracic access to the spine were performed by Hodgson and Stock in 1956 for the treatment of spinal tuberculosis (Pott’s disease) [4]. Since then, advances in surgical technique and instrumentation have dramatically reduced the morbidity and mortality of this procedure, making it one of the first choices in many clinical situations. The main disadvantage of this procedure is related to the potential pulmonary morbidity of a thoracotomy and the possible need for a second operation in case decompression and stabilization of the posterior elements of the spine are needed.

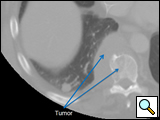

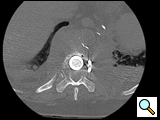

The thoracic spine can be approached through the right or left chest and communication with the spine surgeon is mandatory so that the approach and extent of exposure can be tailored appropriately. In the absence of lateralizing pathology, either a right or left-sided thoracotomy can be used to expose the thoracic spine. As a general rule, the upper thoracic spine (T2-9) is better approached from the right side because of the location of the heart, aortic arch and great vessels. Conversely, in the case of the thoracolumbar spine (T10-L2) a left-sided thoracotomy is preferred to avoid liver retraction. The side of approach must provide maximum exposure to the pathology to be treated. Local factors such as previous thoracotomy, pleurodesis, or infection should also be considered. In general, a right sided approach provides more direct access to the spine, as the mediastinal structures lie to the left of the vertebral bodies. CT and MRI allow for a precise evaluation of the anatomy of the spine pathology and the related intra-thoracic structures (Figures 1a, 1b).

A physiological assessment of pulmonary and cardiac function is best undertaken by the thoracic surgeon, starting with a clinical evaluation and proceeding to PFTs including DLCO, and infrequently a V/Q scan. The pulmonary evaluation determines the patient’s ability to tolerate prolonged single lung ventilation, may help in deciding which side to approach the spine, and aids in predicting postoperative pulmonary recovery and complications. A cardiac evaluation is performed if the patient has multiple risk factors for cardiac disease, known coronary artery disease, or heart failure. Every effort is made to risk stratify the patient prior to thoracotomy for both cardiac and pulmonary complications and institute measures for risk modification. Communication with the spine surgeon is essential to obtain an appropriate risk benefit ratio for each patient from the perspectives of their cardiopulmonary status and spine condition.

Operative Steps

Single lung anesthesia with intra-operative monitoring routinely used for thoracotomy is standard. Adequate large bore (16-14 gauge) IV access is mandatory as blood loss can be substantial during the spinal procedure. The patient is positioned in the lateral decubitus position (Figures 2a, 2b), with shoulders and hips perpendicular to the floor. This facilitates intra-operative imaging of the spine and allows for spinal stabilization in correct anatomic alignment. All pressure points are appropriately padded.

|  |

| Figure 2a: Patient position for thoracotomy, posterior view | Figure 2b: Patient position for thoracotomy, posterolateral view |

|

| Figure 3: Extended surgical field |

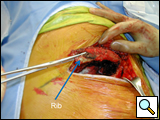

T1-T4 exposure

A high posterior thoracotomy incision is made from the C7 spine, extending between the spine and scapula, to end at the inferior angle of the scapula. Since most of the exposure is needed posteriorly, the incision is extended anteriorly only as needed. The latissimus and trapezius are divided as are the rhomboids and both teres (Figure 4). The scapula is mobilized from the chest wall and elevated using a scapula retractor. An incision is made in the second intercostal space to enter the thoracic cavity or, if a bone graft is needed, the third rib is excised (Figure 5). The erector spinae can be mobilized superiorly and inferiorly to allow for the intercostal space to be retracted, or may simply be divided transversely at the level of the intercostal incision. If necessary, posterior osteotomies of the 2nd and 3rd ribs are made to allow for more retraction of the intercostal space. A Finochietto or Burford retractor (long blade superiorly) can be used to retract the ribs and the scapula (Figures 6a, 6b). Alternatively, a Rultract retractor can be used to elevate the scapula anteriorly and a Finochietto used to retract the intercostal space. A smaller Finochietto rib retractor can be placed placed in the line of intercostals space to retract the soft tissue at the ends of the incision to further improve the exposure. The superior and posterior aspects of the hilum are mobilized and the lung packed out of the operative field with wet lap pads. The vertebral levels are identified and the spine surgeon makes a visual inspection to assess the intrathoracic exposure (Figure 7a). Opening the retractor a few ‘clicks’ at a time every few minutes gradually widens the operative field to allow direct access to the spine. The mediastinal pleura just anterior to the vertebral body is opened vertically from the thoracic inlet to the level of the carina. Using a right thoracotomy the esophagus and azygos vein are mobilized anteriorly using a combination of blunt (finger or peanut) and sharp dissection (Figure 7b). This dissection allows exposure of the entire vertebral body. Venous tributaries of the azygos at this level are ligated and divided. If a left thoracotomy is used the descending aorta is mobilized anteriorly. Ligation of the intercostal arteries at these levels is done after consultation with the spine surgeon in order to limit possible spinal cord ischemia. The major radiculo-medullary artery of Adamkiewicz arises on the left side between T9 and L2 in 60% cases and should be preserved to avoid possible spinal cord ischemia. Mattress stay sutures of 2-0 silk on the anterior cut edge of the pleura help in exposure of the vertebral body and retract the esophagus or aorta away from the spine.

T5-8 exposure

A posterolateral thoracotomy is performed with the incision beginning at the level of T4 posteriorly, extending midway between the spine and scapula, and ending at the inferior angle of the scapula. The latissimus and trapezius muscles are divided and the serratus is spared. The chest is entered through the intercostal space or the bed of the rib at the level of the primary vertebra of interest. Retraction of the intercostal space is performed as previously described. The pulmonary ligament is mobilized and the mediastinal pleura posterior to the hilum is divided from the inferior pulmonary vein to just above the mainstem bronchus. This allows the lung to be displaced anteriorly and packed out of the field. The mediastinal pleura just anterior to the vertebral bodies is opened vertically for exposure of the appropriate vertebrae. The dissection and mobilization of the mediastinal structures is as previously described. On the right the azygos vein with tributaries, the esophagus, and the thoracic duct will mobilized anteriorly. On the left the descending thoracic aorta is mobilized.

|

| Figure 8: Diaphragm retraction |

A posterolateral thoracotomy is performed with the incision originating at the level of the T8 spine and extending forward in a gentle curve along the line of the rib. The muscles are divided and entry into the chest is as previously described. The pulmonary ligament and hilar pleura are mobilized as described previously and the lung is packed out of the way with wet lap pads. The diaphragm obscures the view of the vertebrae at this level and retraction to allow for exposure is mandatory. This can be done with a sponge stick or using horizontal mattress stay sutures of 0 prolene or silk that are clipped to the drapes or sutured to the edges of the thoracotomy incision (Figure 8). The posterior attachments of the diaphragm are mobilized to allow for increased exposure of the T12 and L1 vertebrae. The posterior mediastinal structures are mobilized to permit anterior retraction as previously described.

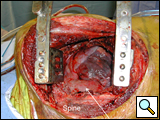

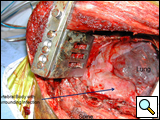

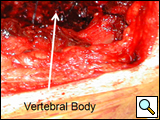

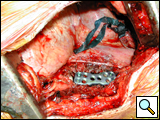

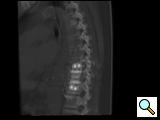

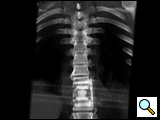

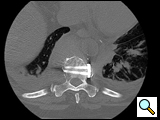

After completion of the spinal procedure, reorientation of the thoracic surgeon by the spinal surgeon is performed, including visualization of the implanted hardware and an explanation of the procedure that was performed (Figures 9a-c). Hemostasis is secured, the chest irrigated, and the posterior mediastinum is inspected for lymph leak (the presence of a CSF leak must be ruled out by the spine surgeon prior to this point in the operation). The diaphragm, if mobilized, is reattached to the fascia of the posterior chest wall with interrupted horizontal 0 prolene sutures or is anchored around the rib. A 28 Fr chest tube is placed in the posterior mediastinum and the chest is closed in a standard fashion. Postoperative spine imaging is necessary to demonstrate adequate position of the hardware and correction of the vertebral defect (Figures 10a-e, Video).

|  |  |

| Figure 9a: Resected vertebral body | Figure 9b: Prosthetic vertebral body placement | Figure 9c: Vertebral fixation plate |

|  |  |

| Figure 10a-e: CT of spine after fixation | Figure 10b | Figure 10c |

|  | |

| Figure 10d | Figure 10e |

Tips & Pitfalls

- Review the CT scan and MRI, and discuss the procedure with the spine surgeon preoperatively.

- Make a physiologic assessment of the patient.

- Make the thoracotomy incision more posterior than anterior.

- Enter the chest at the vertebral level of primary interest.

- Mobilize the pleura of the posterior hilum and divide the pulmonary ligament to allow the lung to be retracted out of the operative field.

- Use stay sutures on the mediastinal pleura and diaphragm to improve exposure of the vertebral bodies.

- Ligate all veins while exposing the vertebrae.

- Ligate intercostals arteries after consulting with the spine surgeon.

- Communicate with the spine surgeon intraoperatively.

Results

There is relatively little in the literature regarding the specifics of a thoracotomy for spine exposure. However, there appears to be an increasing trend for use of an anterior approach to the spine via thoracotomy, and therefore it should be incorporated into the armamentarium of the general thoracic surgeon [5]. Since the most prevalent complications after this approach are pulmonary, particular care must be paid to the preoperative selection of these patients in terms of their pulmonary function and measures to decrease these must be instituted preoperatively [6]. An individualized approach to the level of the spine that is to be exposed reduces chest wall trauma. Careful ligation of intercostal vessels, avoidance of thoracic duct injury, and orientation of the spine surgeon to the relations of the aorta and esophagus to the vertebral bodies further decrease the incidence of a vascular complication, chylothorax and esophageal injury [7, 8]. Postoperative attention to pain management, pulmonary toilet, and ambulation (if possible) help prevent atelectasis and pneumonia. Postoperative hemothorax should be managed with drainage and antibiotics and a low threshold for re-operation. Empyema is managed similarly; however, it is unusual to have to remove the hardware. This decision is usually left to the spine surgeon.

A tailored thoracotomy made to provide optimal exposure of a vertebral level is best performed by a thoracic surgeon who is familiar with the anatomy of the chest and is capable of managing the postoperative intrathoracic complications that may arise.

References

- Christie SD, Song J, Fessler RG. Fractures of the upper thoracic spine: approaches and surgical management. Clin Neurosurg 2005;52:171-6.

- Gokaslan ZL, et al. Transthoracic vertebrectomy for metastatic spinal tumors. J Neurosurg 1998;89:599-609.

- Steinmetz MP, Mekhail A, Benzel EC. Management of metastatic tumors of the spine: strategies and operative indications. Neurosurg Focus 2001;11:e2.

- Hodgson AR, Stock FE. Anterior spinal fusion: a preliminary communication on the radical treatment of Pott's disease and Pott's paraplegia. Br J Surg 1956;44:266-75.

- Ikard RW. Methods and complications of anterior exposure of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Arch Surg 2006;141:1025-34.

- McHenry TP, et al. Risk factors for respiratory failure following operative stabilization of thoracic and lumbar spine fractures. J Bone Joint Surg 2006;88:997-1005.

- Borm W, et al. Approach-related complications of transthoracic spinal reconstruction procedures. Zentralbl Neurochir 2004;65:1-6.

- Oskouian RJ, Jr, Johnson JP. Vascular complications in anterior thoracolumbar spinal reconstruction. J Neurosurg 2002;96(1 Suppl):1-5.